Strengthening Coaching Through an Understanding of Cultural Capability

Strengthening Coaching Through an Understanding of Cultural Capability

This paper is the result of a collaborative writing process by our partners at Growth Coaching New Zealand in association with The Education Group - Dr Nicky Knight, Roween Higgie, Jan Hill, Dr Kay Hawk and Julie Shumacher.

Ehara taku toa i te toa takitahi,

engari he toa takitini

I come not with my own strengths but bring with me the gifts, talents and strengths of my family, tribe and ancestors.

This whakataukī[1] reflects on success being not the work of an individual, but the work of many. As well as the contributions from our Education Group team, we acknowledge the support and lessons we have learned from and with our colleagues and students in the schools, kura and whanau with which we work.

Our Context

We know learners of all ages can flourish in a culturally responsive environment. This article describes our uniquely Aotearoa New Zealand journey of discovery for our team at The Education Group to enrich coaching conversations through an understanding of cultural capability. We want to acknowledge that this is work in progress and we still have a lot to learn and understand. We have each had our own journeys to get to this point. We have needed to be open, curious, patient, and respectful of things we haven’t fully understood. Other people will find their own paths.

In recent times, the New Zealand Ministry of Education has put considerable focus on providers of professional learning and development to schools being culturally capable. New Zealand is an ethnically, culturally and linguistically diverse country, however there is, first and foremost, a strong focus on biculturalism, acknowledging Māori as tangata whenua - our people of the land. Our context is also framed by Te Tiriti o Waitangi, a founding document signed in 1840 that has helped the treaty partners - tangata whenua (Māori) and the Crown - understand their obligations and rights as equal partners. This partnership hasn’t always been an easy one and for decades Te Tiriti o Waitangi was not honoured.

There are Māori concepts/values/uara that, we believe, reflect the essence of being culturally capable in a coaching conversation which include:

- Ako: Sense-making is dialogic, interactive and engaging

- Whakapapa: Culture counts- learners’ understandings form the basis of their identify and learning

- Whanaungatanga: Belonging-relationships of care and connectedness are fundamental. Building relationships first is the key to being successful. “People self-actualise in relationships.” Spiller et al, (2015, p. 87)

- Wānanga: A ‘safe place’ to have conversations based on problem solving and innovation

- Manaakitanga: The process of showing respect, generosity and care for others, also acknowledgment and practice of tikanga and kawa[2]

- Hūmārietanga: Humility- Kāore te kumara e kōrero ana mo tōna ake reka - the kūmara doesn't speak of its own sweetness. This is an encouragement to be modest and show humility. It speaks of the contributions/mana of others.

- Pono: Integrity

Two years ago, we sought permission from Christian van Nieuwerburgh to change one of the components of a coaching way of being from ‘interculturally sensitive’ to ‘cultural capability’ as shown in the diagram below. We know there are many similarities between the two concepts, however, we hope this article helps explain why we wanted to make this change for us in Aotearoa New Zealand and how an understanding of cultural capability adds considerable depth and value to any coaching conversation.

Adapted from van Nieuwerburgh (2020)

Our focus is also supported by the OECD, which actively promotes cultural capability through its dimensions of global competence. “Global Competence is a multi-dimensional construct that requires a combination of knowledge, skills, attitudes and values successfully applied to global issues or intercultural situations. Global issues refer to those that affect all people and have deep implications for current and future generations. Intercultural situations refer to face-to-face, virtual or mediated encounters with people who are perceived to be from a different cultural background” (OECD, 2018, p. 1)

What does it mean to be culturally capable?

We found cultural capability a challenging concept to define succinctly. To help us understand what it meant, we read literature and research, talked to people - Māori (kanohi ki kanohi[3]) and non-Māori - and explored various online platforms, including those from government agencies. We also drew on our many years of experience of working in schools and kura with leaders and teachers. These are our understandings:

All people are culturally located. Culture forms the basis of a person’s identity and learning. We believe being culturally capable is one of the foundations of successful relationships and learning. Our understanding of cultural capability at a broader, systems level, not specifically related to coaching, in Aotearoa New Zealand focuses on

- understanding, valuing and amplifying different world views, perspectives, experiences, and measures of success.

- strengthening our commitment to Te Tiriti o Waitangi and to Aotearoa New Zealand’s histories.

- recognising diversity of identities – including culture, gender, sexuality, ability, and to take action to amplify the views of those and their communities who have been marginalised.

- being aware of practices that perpetuate discrimination, racism and inequity.

- analysing and adjusting practices to communicate and teach in ways that develop critical consciousness and sustain and value cultural identity.

- stepping outside of what we know as educators and learning communities, considering new lenses and ways of looking at things and being OK about making mistakes.

- locating knowledge that has been marginalised and connecting with and legitimising this knowledge

- reflecting critically on the imbalance of power and resources in society, and supporting people to take critical action in their work in pursuit of equity

- understanding the impact of colonisation and its effect on indigenous peoples

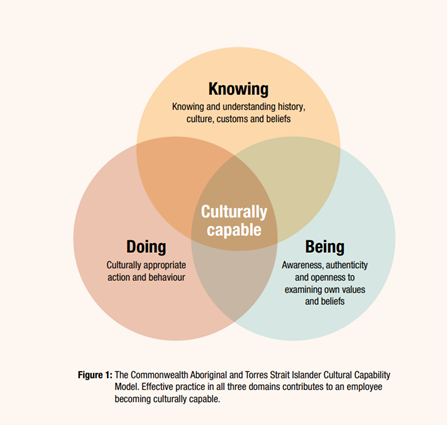

At a more pragmatic level, cultural capability focuses on what you know, what you do and how you are. We have found this framework of knowing, doing and being, from an Australian Government publication created for Commonwealth Agencies ‘Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island Cultural Capability’ useful in framing our understanding.

Commonwealth of Australia (2015, p. 3)

Knowing is committing to ongoing learning of cultural knowledge. Doing is acting in a culturally appropriate manner, embodying a culture of care and Being is demonstrating authentic respect for culture in all interactions, being aware of personal values and biases and their impact on others and having integrity and cultural sensitivity in decision-making. The writers describe cultural capability “as a process of continuous learning” Commonwealth of Australia (2015, p. 4). So do we!

Bishop (2019), a noted New Zealand expert in this area, believes people often confuse cultural competency with knowing about people’s cultures. A culturally competent approach produces anxiety amongst people of getting it wrong, and can promote stereotyping, reductionism and mimicry. A more culturally responsive approach (more closely aligned with our understanding of being culturally capable) includes “learners in their own determination” (Bishop, 2019, p. ix). It is impossible for us to have an in-depth knowledge of all cultures-people are already experts in how they see the world.

Being Culturally Capable in a Coaching Conversation

The Māori concepts/values/uara listed at the beginning of the article along with other background information has culminated in our current thinking about how we could possibly use this knowledge in our coaching conversations.

Understanding Yourself (Coach)

To strengthen your cultural capability, understand who you are as a person.

- Have an awareness of your own cultural identity, cultural practices, values, beliefs, behaviours and assumptions. Be able to tell your story.

- Actively acknowledge, model and act upon the principles of Te Tiriti o Waitangi - partnership, protection and participation.

- Understand your biases and assumptions – any attitudes or stereotypes that affect our understanding, actions and decisions in an unconscious manner. Actively take responsibility for actions to rebalance personal views and decisions. Be prepared to be challenged and contribute to discussions about beliefs, attitudes and values.

- Address your own learning needs specific to the use and pronunciation of Te Reo Māori or other languages appropriate to your context. Do this with authenticity and integrity.

- Address your own knowledge gaps by engaging in targeted professional learning and development specific to the cultural practices of relevant groups. Access ongoing cultural mentorship to develop cultural understanding. For us in Aotearoa New Zealand this is Māori first and then other ethnic groups

- Maintain respectful eye contact. In some cultures, looking down when talking to someone is a sign of respect.

- Model inclusive practices

- Respect tikanga[4]

Beginning Your Coaching Conversations

- We see coaching as a reciprocal learning process (Āko). Ask your coachee how they would like to start the coaching session. It might be sharing information about each other, and/or with a karakia[5] or a blessing in Aotearoa New Zealand.

- Create an environment of relationship-based learning in the coaching relationship so that coachees are “enabled to bring their cultural knowledges, understandings and sense-making processes to the forefront” (Bishop, 2019, p. xi). Our concept of whanaungatanga defined as relationships of care and connectedness is fundamental to successful coaching conversations. This involves the coach asking questions to understand the coachee’s current reality:

- Know and affirm who I (coachee) am – my whakapapa (genealogy), language, culture, identity and family

- Know who comes with me – who are the important people in my life that have helped me get to where I am today? Who has been influential in my journey to date? Acknowledge that there are differences and commonalities between people.

- Nourish my uniqueness

- Give the coachee an opportunity to get to know the coach. A coachee once said, “Well I have told you all about me so now I want to know about you!”

- Use and show respect for the indigenous language. Pronounce names and words correctly and ask for help if necessary. Acknowledge that you may not have the correct pronunciation, however you are on a journey of learning.

- In the first coaching conversation make direct links to information that is included in any background information gathered by the coach about the coachee. Having an awareness and being responsive builds the “relationship of trust, support and mutual respect” to have effective coaching conversations (Timperley, 2015, p. 23).

- Explain what this coaching opportunity will involve and how you both might work together to ensure that the experience is valuable for the coachee. Ask the coachee how they want the relationship to work.

- Build an understanding of the coachee’s aspirations for being involved in this coaching experience

- Agree on the best way to work together e.g., listening, being honest, being comfortable to ask the coach to clarify something at any time, minimal eye contact, needing time to think.

- Reflect on how our own cultural capital might be influencing our interactions with others

During Your Coaching Conversations

- Draw on and build on the coachee’s prior knowledge and experiences which Bishop (2019) says is “fundamental to interactive, dialogic approaches.” (p. 79)

- Search for elements in stories relayed by your coachee that invite “challenge, redefinition or interpretation so a re-framing of the problem can occur.” (O’Toole, p. 10)

- Be non-judgemental, a learner and demonstrate curiosity

- Acknowledge progress and evidence of the goal being achieved

- Be open to different points of view and perspectives

Ending Your Coaching Conversations

Ensure the coachee is clear on their next steps and that they are confident moving forward. Questions for the coachee to ask of themselves

- Do I believe that I can do this? (Mana wairua)

- Do I have the resources? (Nga rauemi)

- Do I have the support? (Tautoko)

- Can I cope with the demands/mahi? (Te kaha-strength in many areas)

Invite feedback from your coachee. “What’s clearer now?” and ask how the coaching experience was for them

Next steps

We are keen to work with local iwi, hapū and mana whenua and have us walk together on this journey to further our understanding. We want to build a relationship with them and ask for their guidance. We expect the relationship to be reciprocal and are keen to know how we can contribute. We want to embed cultural capability in a sustainable way into our organisation and our way of being.

We believe this whakataukī sums up what is at the essence of a coaching conversation; that coaching is about empowering others to help themselves.

Mā te huruhuru ka rere te manu.

Adorn the bird with feathers so it may soar.

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge the following people who have generously shared their knowledge and ideas for this article.

Dudley Adams (Nga Puhi)

Kerry Mitchell

Tom Hullena

Marilyn Gwilliam

David Ellery

Dr Deanna Johnston

References

Bishop, R. (2019) Teaching to the north-east: Relationship-based learning in practice Wellington: NZCER Press

Commonwealth of Australia (2015) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island Cultural Capability

Knight, J. (2018) The impact cycle: What instructional coaches should do to foster powerful improvement in teaching Thousand Oaks, California: Corwin

OECD (2018) PISA Preparing our youth for an inclusive and sustainable world: The OECD PISA global competence framework Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/pisa/innovation/global-competence/

O’Toole, S. (2015) Indigenous mentoring and coaching in Training and Development pp. 10-11

Quinlan, D., & Hone, L. (2020) The educators’ guide to whole-school wellbeing London: Routledge

Spiller, C., Barclay-Kerr, H., & Panoho, J. (2015) Wayfinding leadership: Groundbreaking wisdom for developing leaders. Wellington: Huia Publishers

Timperley, H. (2015) Insights: Professional conversations and improvement-focused feedback. Melbourne: AITSL - Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership

[1] Whakataukī = a Māori proverb or wise saying

[2]Kawa= Māori protocol

[3] Face to face

[4] Tikanga-the right. Acknowledgement of Te Ao Māori (Māori world view)

[5] Traditional Māori prayer